From the desk of Laura A Wallace:

From the desk of Laura A Wallace:

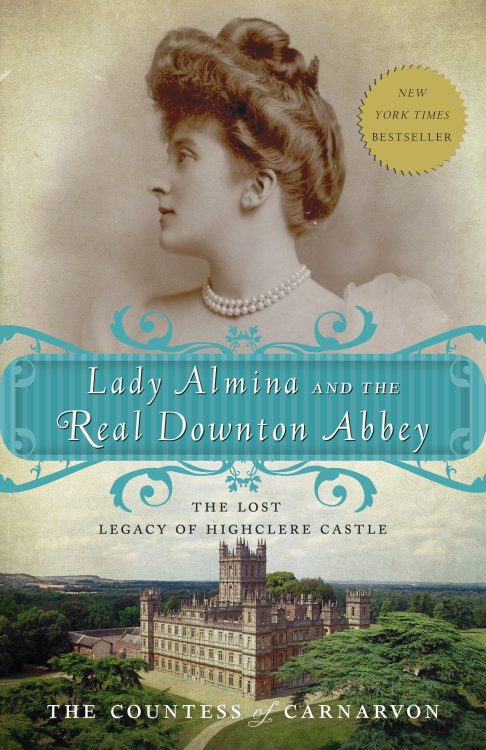

The Countess of Carnarvon has written a biography of one of her predecessors: Almina, Countess of Carnarvon, wife of the 5th Earl of Carnarvon. This book lacks depth but is fairly well written and well researched. It does not purport to be a sophisticated biography, being entirely without footnotes or endnotes, and claims, in the Prologue, to be “neither a biography nor a work of fiction, but places characters in historical settings, as identified from letters, diaries, visitor books and household accounts written at the time.” I found this characterization a little puzzling because it is clearly a biography and does not in any way approach fiction: there is no dialogue and very little in the way of scenes or vignettes. I rather wish Lady Carnarvon had chosen to go in one direction or the other: a meaty, substantive biography or a lighter, fictionalized account. But the result is easy to read and the bibliography, if little else, is substantive (though it seems to me that little of it actually made it into the text).

I can reduce my review to three phrases: (1) Title Abuse; (2) Downton Abbey; (3) Amelia Peabody. I’ll take them in reverse order. To be honest, there is nothing about Amelia Peabody in the book at all. But for those who are fans of hers (I speak of the series of novels written by Elizabeth Peters), the account of Howard Carter’s discovery (along with the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, of course) of the King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 inevitably brings Amelia and her milieu to mind. Having long been familiar with not only Carter but other real people like Wallis Budge and even T. E. Lawrence from the Peabody novels, I felt like an insider when it came to Lord Carnarvon’s archaeological efforts in Egypt. And this book, rather than sending me back to watch Downton Abbey all over again, sent me instead to reread the novels about Amelia Peabody (and Vicky Bliss too).

The Downton Abbey connection (in case you missed it) is that Highclere Castle, the ancestral home of the Earls of Carnarvon, is the filming location for Downton Abbey, which is set contemporaneously with Almina’s tenure as chatelaine of Highclere. The 5th Earl inherited his patrimony at a young age, and soon realized (as did Downton’s Earl of Grantham) that he needed to marry an heiress to secure his estates and lifestyle. But instead of choosing an American heiress, as some other peers of his generation did, Lord Carnarvon selected an heiress from the Rothschild family. To be fair, it appears to have been a love match—she was vivacious, charming, warmhearted, and beautiful, and they seem to have had a long and remarkably happy marriage—but, as with the fictional Granthams, money is what made the love match possible for the Carnarvons. And the house played a great role in their lives.

The first and most obvious difference between the reality of Highclere and the fiction of Downton is that the roles of the servants were substantially reduced and simplified for television. The “mutually dependent community” of Highclere was run, not by a butler, but by a steward. There was also a groom of the bedchambers, butler, under-butler, and of course valets, all above at least four footmen (who powdered their hair to wait at table until 1918), who were above porters and the steward’s room boy (whose primary job was to find and alert the proper staff when one of the sixty-six bells rang). The female staff was likewise magnified, and the division of labor among all these servants was not always the traditionally understood setup as depicted in Downton Abbey. The outdoor staff included not only an estate agent, but gamekeepers, gardeners, coachmen, grooms, stableboys, and people to take care of the automobiles. And that’s just for the house and its immediate environs, not even getting out into the estate’s farms and tenantry. Lady Carnarvon rightly describes the setup as feudal—even though the house itself had been (re)built during the 4th Earl’s lifetime. (The estate had been owned by his family since the late seventeenth century.)

Like Downton, Highclere played a role as a private hospital during the World War I, funded and run by the Countess. But after some months, she decided that the house and location were inadequate and moved her hospital to a house in London in Bryanston Square. She purchased the latest equipment, hired the best staff, and did her utmost to make the officers under her care feel as though they were guests in a private house rather than in an institution. Also like Downton, several members of the estate family volunteered for service and were killed in the war. Many of them belonged to Highclere in a very personal way: they were members of families that had served the estate and the Carnarvons for generations.

My only real complaints about this book are legalistic, so if you’re not one for getting all the tiniest details correct, you can skip this part. The first, and biggest, error is not, I think, all the fault of its author. Lady Carnarvon never makes the egregious mistake of referring to the wife of the 5th Earl, the Countess who is the biography’s subject, as “Lady Almina.” (There seems to be some sort of general but erroneous belief that using “Lord” or “Lady” with the given name is an acceptable not-as-formal usage. It is not. The usage of Lady with the given name is allowed only to the daughters of dukes, marquesses, and earls, and is never used for the wives of peers.) Unfortunately, not only does the title of the book brandish this error across the front cover, but it appears even in the back cover blurbs about the book and its author (who is not “Lady Fiona”), and some of the photo captions. I think these prove that authors ultimately have very little control over the covers of their books.

However, there is another mistake in the text that is on my list of pet peeves as well, and it occurs more than once so it is not just an isolated slip. It concerns Almina’s parentage. Almina’s father was Alfred de Rothschild. He was, unfortunately, not married to her mother, whose husband lived apart from her at the time Almina was born. But these facts did not make Almina “illegitimate.” The only thing that word refers to is the marital status of a mother at the time of birth of her child. It has nothing to do with the identity of the child’s biological father. Almina’s mother was married, so even if everyone “knew” that her husband was not the biological father of her child, legally he was Almina’s father in every way, and she bore his surname. And while it is true that Almina’s actual parentage was somewhat of a scandal, she herself was not beyond the pale. Indeed, as the book recounts, she was presented at court and attended a state ball at Buckingham Palace as a debutante. Her mother’s status, officially and socially, is less clear, but Almina remained close to both of her parents for their entire lives, and they were welcome at Highclere.

Overall, Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey is a good read on the light end of the modern biographical scale, perhaps intentionally reminiscent of the more chatty biographies popular during Alimna’s lifetime.

3 out of 5 Stars

BOOK INFORMATION

- Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey: The Lost Legacy of Highclere Castle, by The Countess of Carnarvon

- Crown Publishing Group (2011)

- Trade paperback (320) pages

- ISBN: 978-0770435622

- Genre: Nonfiction, Historical Biography

ADDITIONAL INFO | ADD TO GOODREADS

We received a review copy of the book from the publisher in exchange for an honest review. Austenprose is an Amazon affiliate. Cover image courtesy of Crown Publishing Group © 2011; Laura A. Wallace © 2012, austenprose.com. Updated 6 March 2022.

I think wives of peers are referred to as ‘Lady,’ though… On Wikipedia it says: “The wives of courtesy peers hold their titles on the same basis as their husbands, i.e. by courtesy. Thus the wife of Marquess of Douro is known as Marchioness of Douro.”

LikeLike

Oh my I must read this book!!! Thank you for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comments!

Yes, the wives of peers are referred to and addressed as “Lady,” But NOT “Lady Firstname.” In the present example, the Countess of Carnarvon is addressed as “Lady Carnarvon.” She would NEVER be “Lady Almina” (or “Lady Fiona”) after marrying a peer, no matter who her father was.

All uses of the title “Lady” are not equal!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know this book was released in the UK first, so why the heck didn’t they get the Lady stuff right? Amazing oversight.

Thanks for the great review Laura.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thoughtful review. I am looking forward to reading it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am nearly finished reading this book. It is an easy read; however, it leaves a desire to learn more about the people depicted in the narrative. One subject the Countess thoroughly details is “The Great War.” The affect on the inhabitants of the Estate and the country as well as many of the military movements on the contintent and in the Middle East are very detailed. Perhaps that was more of an interest to the author or more easily abtained information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have read this and the sequel biography on the 6th countess. I agree with you that the main mistake of the book is in the title -referring to the 5th countess as “Lady Almina” which is incorrect. The current Lady Carnarvon repeats the same mistake by referring to Almina’s successor as “Lady Catherine” and its not helped by the UK media even mistakenly referring to real life peeresses in the same erroneous fashion such as “Lady Karren” rather than “Lady Brady” or “Baroness Brady”.

The book is an interesting read but there is little to no analysis. One interesting point however is it does shed light on aspects of the aristocracy and the First World War that Downton Abbey has omitted such as the more elaborate hierarchy downstairs as well as how the 5th earl and countess were active and willing with regards to their participation in the war effort something that the fictional Granthams lacked. This flies in the face of historical reality when real life peers, peeresses and their families were the first to enlist and volunteer their services to the war effort.

If you are interested in the real history behind the this book and Downton Abbey then David Cannadine’s The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy is a good starting point. Be warned though, its quite weighty and contains a lot of end notes and an extremely long bibliography.

LikeLiked by 1 person