Getting the historical details correct is so critical in period drama today. Gone are the days when Greer Garson could wear a hoop skirt in the 1940 Pride and Prejudice and get away with it. The production team of the new BBC/PBS Poldark, at Mammoth Screen Ltd., have stepped up to the mark depicting late eighteenth-century Cornwall, warts and all. Advising them in this monumental task is lecturer, author, and historian Hannah Greig who joins us today to answer a few questions about her role in the production of Poldark and the historical context that it is set in.

LAN: Welcome Hannah. One has visions of historians entrenched in musty library stacks secretly pining for their favorite reference librarian! Besides teaching and writing, you have carved out an interesting niche as Historical Advisor for films, television and theatre. This seems like a very glamorous job. Can you share with us what your duties are, what a typical day would be like, and what kind of questions are asked by the production team?

HG: Historical advisers are more geek than glam! Before filming begins, I’ll check the script for anachronisms, write history crib notes, and tackle questions from the production team. These range from discussions about particular props to contextual information, like whether or not people in Cornwall would have been aware of events in America. If there is a bit of rehearsal time I’ll join the cast to run history-related Q&As. Normally I’ll turn up to a room full of people I’ve never met before but Poldark was a nice change because I’d worked with some of the cast and crew on Death Comes to Pemberley (Eliza Mellor, producer; Marianne Agertoft, costume designer; and Eleanor Tomlinson who played Georgiana Darcy before Demelza). Coincidently I also knew Andrew Graham from my academic guise. He was master of Balliol College, Oxford, where I held a history post for a while (in fact he had interviewed me for the job). I’d last seen him at Balliol’s high table and I hadn’t known that he was Winston Graham’s son, so it was a lovely surprise to find him in the very different setting of the Poldark rehearsal room.

Once filming starts, the pace is frenetic for everyone else but calms down for me. By then it is too late and too disruptive to dish out history lessons (and I try to avoid being the stereotypical “hysterical adviser”). Although I love to see the eighteenth century come to life, I’m only any use to the production if there are big set pieces being filmed, like ball scenes or street scenes. If I am on location then you’ll probably find me begging a tour of the props trailer, which is like a curiosity cabinet stuffed full of exciting things. If I am not on set then I am still on call for the duration of filming, and available on the phone for any last minute questions. I always check the schedule every morning to see what is happening so that I can give a quick answer if someone rings in a question. (Ralph Fiennes once called me unexpectedly from the set of The Duchess when I was in an Oxford supermarket – fortunately I managed to answer his questions whilst buying my milk).

LAN: You have worked on some of my favorite Georgian period dramas: The Duchess, Death Comes to Pemberley and now Poldark. You specialize in eighteenth-century British history. What intrigues you about this era of history?

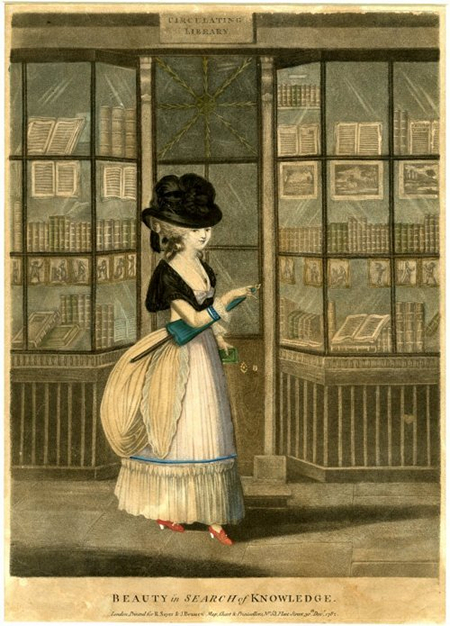

HG: I think I was first drawn by the literature, art and also the satirical culture of the time. There seemed to be such a cacophony of voices – chattering through eighteenth-century newspapers, manuscript letters, plays, poems and novels – and I simply wanted to make sense of it and hear what everyone had to say. I am fascinated by the small details of social performances. I’m pretty confident that I could navigate my way through the complexities of an Almacks’ assembly or even sneak into George III’s birthday ball without being found out as a time traveller.

LAN: Captain Poldark returns home to Cornwall in 1783, a historically significant year for Great Britain. What was the economic, political and social atmosphere in the UK during this time, and how did it impact the Poldarks and other Cornish landed gentry?

HG: It is a time of marked economic, political and social change, the perfect setting for drama. Eighteenth-century Cornwall is particularly interesting. Its ports opened to a wider world but those routes were disrupted by wars. Its mineral reserves and fish stocks underpinned the regional economy, yet they had become increasingly scarce as the century progressed. The fact that Cornwall had 44 MPs at the end of the century reveals how incredibly important it had been as an economic and political unit for previous generations. By then, however, such a disproportionately high number of MPs in a sparsely populated region was being cited as evidence that the political system was in dire need of reform. Outsiders saw Cornwall as unique. One traveller described Cornish miners as “a race distinct from others … governed by laws and customs almost exclusively their own.” It was a place that commanded loyalty and a defining sense of identity. Graham captures this masterfully in his books, and then Debbie Horsfield skillfully brings it all to life in vibrant scripts full of Georgian bon mots.

LAN: Through the female characters of Elizabeth Poldark, Verity Poldark and Demelza Carne, we see the stifling social strictures placed on women in 1780’s England. Why would Elizabeth choose to marry a man she did not love, Verity become a servant in her own household and Demelza tolerate abuse from her father?

HG: These three characters encapsulate contrasting elements of Georgian womanhood. Heida Reed (Elizabeth), Ruby Bentall (Verity) and Eleanor Tomlinson (Demelza) do such a great job of capturing their complexities. Elizabeth and Verity’s stories are ones that might have interested Austen. Elizabeth wrestles between practical and passionate expectations. She has no idea that Ross would ever return from war. Francis is the viable alternative – young, attractive and heir to a substantial estate. On paper, what’s not to like? Ross is a far more dangerous prospect: a risk taker with an unpredictable disregard for social norms. However, the choice that Elizabeth thinks she is making is not between Ross and Francis, but between a well-matched marriage and life as a single woman. Verity’s dependence on her male family members as benefactors reminds us how little power unmarried women had at the time. She can’t work and so her only hope for security is to be indispensable at home, a role threatened by her brother’s marriage because Elizabeth immediately outranks her as mistress of the house. Demelza’s story is the dream that would not have happened in reality. It would have been unthinkable for a gentleman to marry his kitchen maid (although it was an escapist fantasy that made Samuel Richardson’s eighteenth-century novel, Pamela, a best seller). For Demelza, it is not so much a question of tolerating abuse but rather of having no other options. Had she not met Ross so unexpectedly, what path might she have taken? Fortunately, we don’t need to worry about that because Ross – being Ross – defies all convention and marries her.

LAN: Gentlemanly pursuits in late eighteenth-century England can seem excessive to modern day viewers. In Poldark, the scenes of cock fighting and dog-baiting are very cringe worthy. In addition, everyone seems to be consuming large quantities of liquor and gambling without hesitation. Can you elaborate on the Georgian view of entertainment?

HG: Betting, drinking, betting, drinking, betting, betting, betting – that is what many a gentleman’s (and lady’s) diary from the eighteenth-century contains. Even the soberest matron seemed unable to resist a little flutter now and again. And some of the “entertainments” that you might find at a fair are so extreme that it not possible to show them on screen. If you were a real stickler for accuracy, you’d be insisting on cock throwing rather than cock fighting with punters throwing stones and sticks at a tethered bird until someone killed it to win the carcass. But if you didn’t fancy stoning a cockerel to death or watching a bare-knuckle fight when you visited a fair, you could always join a sack race or buy some souvenirs instead. There were simpler entertainments that counterbalanced the viciousness.

LAN: In episode two of Poldark, Ross’s lost love Elizabeth, who married his cousin, tells him that she is pregnant. The Jane Austen fan in me gasped when I heard her share such an intimate detail with him. What is the socially-correct way for Georgian ladies to reveal that they are in the family way?

HG: This is a great question. I’d be interested to know what your readers think. As far as I am aware such a conversation would never happen amongst polite society. Manuscript letters reveal that most women waited until they were sure they had felt a “quickening” (i.e. the baby moving) before they confided to family members. Late in pregnancy, women referred to their anticipated “lying in” – which was one way of modestly conveying news that was no doubt obvious by then anyway. But such delicacies do not translate well to the narrative needs of a drama. Sometimes we have to let the Poldarks do things their own way.

LAN: While working with the cast and crew during the production of Poldark, what was the most challenging question you were asked? And, who do you call when you are stumped?

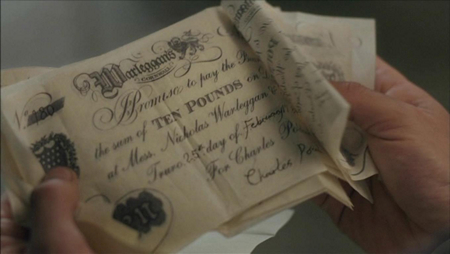

HG: It might not sound like an exciting one, but the toughest question was probably “what would the interior of a bank look like?” Answering it was tricky. It didn’t fit with my own academic work and information about provincial banking is scarce, so I needed to do a bit of digging. In the end, the archivist at Barclays Bank very helpfully gave me the pointers I needed to find a meaningful answer. My university department at York has a large number of scholars specialising in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and I often pump them for information. Dr Mark Jenner gave me some tips about the likely location and features of a pub privy when I was working on Death Comes to Pemberley (key to the plot!). Dr Catriona Kennedy helped me pick through Wickham’s backstory (who P. D. James imagines has been fighting in the Irish Rebellion), and also confirmed details about Ross Poldark’s likely experiences in the American Revolution. Charles Spencer, military curator at Bankfield museum, stepped in to solve some highly specialist questions for Poldark about uniform and battles. And my students are always keen assistants if I need to hunt down extra source material (they all want my job). When a film or television production is being scripted or shot I can’t reveal much about the project, and so I’m very grateful to all these contacts for tolerating the seemingly bizarre and cryptic questions I fire at them.

LAN: Napoleon Bonaparte said, “History is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon.” As most savvy period drama fans know, filmmakers often make artistic decisions to suit their needs. As a historian, what are your views on the compromises needed to make historically based productions appealing and relevant to modern viewers?

HG: For me it is important that ideas about history extend beyond surface detail. I think it can sometimes be too easy for everyone (cast and crew, the audience, critics and myself included) to focus exclusively on set dressing and costume, as if all the secrets of the past reside there. Whilst these elements are paramount in transporting the audience to a different time and place, so too are the less tangible historical contexts – the circumstances that changed people’s outlook, that challenged their identities and that motivated their choices in life. History is about more than getting the right kind of cutlery on the dinner table. If we only ever focus on the specifics of a period look then the essential importance of history to developing character and context can too easily be forgotten or undermined. Poldark does a great job of getting that balance right.

LAN: You studied under one of my history icons, Amanda Vickery. I understand that you both visited the set of Poldark during filming. What are your impressions of that day? Can you share any anecdotes, and a picture?

HG: I would love to provide you with a picture of Amanda Vickery in eighteenth-century costume at a Cornish assembly but, regretfully, we did not make it on to set. I was in late pregnancy when filming started (in eighteenth century terms, I was approaching my “lying in”) and the 1780s is not a place I’d recommend for pregnant women. However, we were lucky to have Amanda with us for a history Q&A in the rehearsals. We talked a lot with Aidan, Eleanor and the rest of the cast about the nature of the eighteenth-century social hierarchy, and why Ross’s marriage to Demelza was such a radical breach of convention. In discussion I think we covered everything else from etiquette to the economy and how often servants got drunk (that bit was especially for Prudie and Judd). The Poldark cast were excellent students, and tolerated our teacherly-ness with good humour and lively enthusiasm. I’ve promised Amanda a set visit once series two is filming. If we make it to Nampara later this year, we’ll be sure to send you a picture, especially if I can persuade Professor Vickery into a mantua or bal maiden’s cap.

LAN: We could not conclude our discussion today without mentioning your fabulous first book, The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London. I found it fascinating. Informative and engaging, Jane Austen and Georgian history fans will devour this with pleasure. Are you working on another book, and if so, can you share any details?

HG: Thank you for the kind comments about The Beau Monde. In that book I tried to dispel some stereotypes and give the more serious take on London’s fashionable set, but without stripping those notorious lords and ladies of all their allure. I have a few new projects that I’m developing at the moment, including a biography of a famous and charismatic eighteenth-century gentleman. I can’t say more than that yet, but I’m already enamoured with him. I’ve also got some shorter pieces of academic work to finish up on eighteenth-century masquerade dress and diamonds. It is probably not hard to tell that my interests run close to Austen with a little dash of Fanny Burney and Anthony Trollope on either side. Before I can get to my writing, though, I’ll be reading Debbie Horsfield’s scripts for Poldark series two, which will be on my desk soon. I can’t wait to see where she takes us next.

LAN: Many thanks for your time Hannah. We are looking forward to your next book, and of course the next season of Poldark in 2016.

Hannah Greig flanked by redcoats of the 33rd Regiment of Foot filming Death Comes to Pemberley.

HISTORIAN BIO

Dr. Hannah Greig is the author of The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London (Oxford University Press, 2013). She is a senior lecturer in history at the University of York, UK, where she teaches eighteenth-century British social, cultural and political history. Before joining York she held academic posts at Balliol College, Oxford, and the Royal College of Art, London, and completed her PhD at the University of London.

An authority on Georgian Britain, Hannah is an established historical consultant for film, television and theatre. Credits include the feature film The Duchess (Qwerty Films 2008, directed by Saul Dibb). Jamie Lloyd’s production of The School for Scandal (Theatre Royal in Bath, 2012), and BBC television dramas Death Comes to Pemberley (2013), Jamaica Inn (2014), and Poldark (2015). She lives in London and York.

Be sure to follow Hannah on twitter as @Hannah_Greig.

Poldark production images courtesy of Mammoth Screen, Ltd. for Masterpiece PBS © 2015; text Hannah Greig © 2015, austenprose.com.

Fascinating interview. I love the series and have read the novels. Thanks so much for a wonderfully informative and enjoyable visit behind the scenes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderfully interesting interview, thanks. I laughed at the part about the bank, because in my book I desperately wanted my characters to go to a London bank in 1815 — but I could never track down a picture or description! So I had to leave out the scene.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow love the info on this i am enjoying watching the show i am so inlove with the characters especially ross and demelza i have the dvd from pbs and cant wait for the second season to be out i know i have to wait until 2016 booo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the fascinating look behind the scenes! I love the Poldark series. I can’t wait to read the books. :)

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a superb interview! Thank you so much, Laurel Ann.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was an enormously wonderful and enlightening interview detailing eighteenth century England. Their entertainment preferences were odd indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this entertaining and informative interview…it makes me want to own The Beau Monde even more now! I attempted to find it at my independent bookstore, but apparently another Austenprose reader got there first and bought the only copy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL Greta!!! One likes to envision hordes flocking to books stores because of my reviews and writing, I give all the credit to the incredible authors.

LikeLike

Wonderful interview! Thanks so much for sharing. Love knowing the history behind this story I’m coming to love!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Laurel Ann; that was fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m delighted that British television producers, at least, care about historical accuracy. I’m not a specialist myself, but I’ve seen cringeworthy anachronisms in some American programs that supposedly take place in the past, not to mention inaccurate portrayals of other cultures and/or languages.

LikeLike

While I realize that Ms. Greig was trying to play down the more exciting aspects of being a historical adviser for film and television, I can only say that getting a phone call from Ralph Fiennes would pretty much make my year! Fascinating interview, Laurel Ann!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I LOVE the Poldark series too; best series since Downton Abbey, and hope it has a LONG run.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do like to read of history connected with favorite stories but am no expert so “thank you” for helping those movies or TV series give a fairly true picture of the time they are set in. I am enjoying this series but have yet to read the books and missed the series in the 70’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the insight into 18th century life

Fascinating informatipn into the culture then.

LikeLike

There was one major inaccuracy. In the 1700 hundreds and into the 1800 hundreds they used midwives, not doctors. The use of doctors came later in the 1800 hundreds, when doctors elbowed midwives out, and childbirth deaths increased as a result. Susan Rechen

LikeLike