From the desk of Br. Paul Byrd, OP:

From the desk of Br. Paul Byrd, OP:

It was about thirteen years ago when I first met and fell in love with Jane Austen. I was up late flipping through the channels on T.V., when I came across the 1996 adaptation of Emma starring Kate Beckinsale. From the moment I began watching the story about this self-absorbed, charming busybody, I was hooked. I went to the library the very next day to check out the novel, and went on to read Austen’s other five major works. By now, I have reread all of the novels, watched most of the film adaptations, peaked into some of the sequels and spinoffs, studied many of the commentaries, and have even gone on pilgrimage to Chawton, Bath, and Winchester. Like so many others, I have a devotion to Blessed Jane.

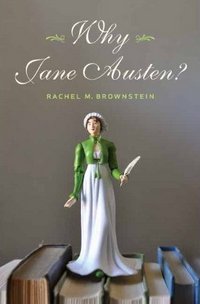

If you can relate to the above confession, then you will want to read Rachel M. Brownstein’s intelligent, insightful, and illuminating new book Why Jane Austen, a work that explores the origins and characteristics of what the author calls “Jane-o-mania.” She writes in her introduction:

“The pages that follow are experiments and explorations in what might be called—if the term is broadly defined—biographical criticism. I am interested in why Jane Austen is on our minds now, and in her relationship to her characters and her readers…” (12)

Brownstein’s project is an intricately accomplished one, and perfect for either the seasoned Austen scholar or the neophyte groupie eager to learn more. Within the five chapters of the book, she weaves commentaries on the entire Austen canon, including lesser known works like Lady Susan. Brownstein’s thoughts are disarming at times, due to the wisdom that comes from teaching for quite a while. Her questions about the famous opening line of Pride and Prejudice, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife,” for example, made me second guess whether I actually understood it, and for that matter, whether I understood the novel itself. Likewise, she brilliantly noted of Mansfield Park: “…in this novel more than the others, where characters so easily stand in for and replace one another, the narrator seems to mock the very possibility of the unique, complex, important individual self that romantic narrative makes so very much of” (119). In her review of Austen’s oft neglected short stories, she argues they display the early genius at work—a young writer critiquing the English novelists who came before her (181-185). Brownstein’s richest insights, however, are about Emma, a novel seemingly about nothing (plot-wise), but really about the power of language and the importance of speaking the truth (204). Brownstein writes, Emma Woodhouse “goes nowhere, stays the same, resists change” (220), and she wants us to ponder what that means.

Brownstein’s project goes far beyond the actual works of Austen. She presents a survey of the film adaptations of the novels, as well as comments on movies like Clueless and television shows like Lost in Austen that borrow or play with Austen’s standard plot elements. Her review is invaluable for appreciating the breadth of the Austen market. Ultimately, however, Brownstein is critical of the adaptations declaring: “To make movies of Jane Austen’s novels [is] by definition to alter them” (35-36) She argues that the movies, the sequels and prequels and mash-ups and spin-offs, tend to get things wrong by focusing on the landscape—whether we mean the natural wonders of the countryside, the lavishly decorated rooms of a manor house, or the beauties of the human body (35-36), details Austen purposefully made little of. A classic example of adaptation gone wrong is Rozema’s film version of Mansfield Park, where Fanny Price is conflated with Elizabeth Bennet, and even Jane Austen herself (51). Running away with Austen often means leaving her behind.

According to Brownstein, reading the novels is not enough to know or understand Jane Austen. To avoid oversimplification, we must contextualize her, learning the history of Georgian England and reading the authors who inspired or annoyed Austen: authors like, Richardson, Radcliffe, West, Smith, Burney, Fielding, Edgeworth, Wordsworth, and Scott, as well as, other contemporaries like Byron, Wollstonecraft, and Shelley. And we cannot stop there, but ought to read her literary children: authors like Henry James, the Brontes (who rebelled against her), and her literary grandchildren like Ian McEwan, author of Atonement. If you are daunted by this reading list, which should also include Inchbald, Oliphant, Eliot, Forster, and Pym, don’t be; reading Brownstein’s book will give you a great head start.

Furthermore, Brownstein urges us to avoid the pitfall of believing that fiction is merely “veiled autobiography” (25), rather, she insists that the historical Austen eludes us (134). She was an artist, and art is bigger than biography. Indeed, she argues,

“They [Austen’s short stories] make it clear that her literary concerns and techniques are in effect all we know of her, all we can love that we are not making up” (181).

I am not quite with Brownstein on this point, as I believe that in reading the creations of this literary genius, we get a powerful testimony of how she saw the world, what made her laugh or cry, and what she put her faith in—and what is this, but a glimpse into Austen’s essential being?

After masterfully analyzing the original texts, along with their historical context, the important academic interpretations of them, and the on-going life they enjoy in popular retellings, one might ask if Brownstein answers her question, Why Jane Austen? She does. For her, people read and reread Jane Austen, because Austen wrote so convincingly about human nature and the intricacy of character (8, 121), and because her impact on the Anglophone world is extensive, through her perfection of the style of English expression (3). They declare she is to the novel what Shakespeare was to drama (71-72), an artist whose art saves lives (106-107). She was a moralist who did not moralize (199), rather, she teaches readers how to pay attention (202) and to value the intellect over more superficial traits (204). Her works are sources of wisdom not found in information books (234), because she wrestles with the “hard truths and evils of life” that all of her readers of every culture have to face (247). And, in the end, people crave the neatly ordered, comprehensible world she depicts (64).

Brownstein proves all this in language that itself is a delight to read, with interesting stories from her own life and those handed down by the Austen family about Jane. I can only conclude by saying, if you love Jane Austen, you will probably understand why you love her better after having read this book.

4 out of 5 Stars

Why Jane Austen, by Rachel M. Brownstein

Columbia University Press (2011)

Hardcover (320) pages

ISBN: 978-0231153904

Cover image courtesy of Columbia University Press © 2011; text Br. Paul Byrd © 2011, Austenprose.com

Yes! I have read this wonderful book and highly recommend it to any reader who also loves Jane Austen and wants to know more about her. I found a lot of information, insights, and surprises that I had not read about in any other non-fiction account of the “Jane Austen phenomenon.” Excellent review!

LikeLike

insightful review – thank you Br Paul

a new must read ~

LikeLike

Graceful and informative review. For those who have not read any other books by feminist biographer Brownstein, her biography of the great French actress Rachel, entitled “Tragic Muse — Rachel of the Comédie Française” (1995) remains the definitive book on the subject, as well as a thrilling read in its own right.

LikeLike

Enjoyed your review. Thank you. The book does sound interesting.

LikeLike

I’m really interested in reading this book! This is the first I’ve heard of it, but it sounds very cool. A way to get insie my own head.

LikeLike

I can’t wait to read this! I loved Brownstein’s thoughts on Austen in Becoming a Heroine so I’m certainly looking forward to a whole book full of them.

LikeLike

I have this book in my TBR pile. I continue to find that it is going to be a must read. Thank you, Br Paul, for your review!

LikeLike

>Brownstein urges us to avoid the pitfall of believing that fiction is merely “veiled autobiography” (25), rather, she insists that the historical Austen eludes us (134). She was an artist, and art is bigger than biography. Indeed, she argues,

I actually think this is the point that would entice me to read this book–I read Jane’s Fame fairly recently and have been thinking of giving this one a pass, but I so fervently agree with this idea that I am encouraged to give Brownstein’s book a look.

Thanks for a great review–v. interesting.

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading this review and appreciate Br. Paul’s insights. This is a new title to me that will now be in my TBR list. Thank you!

LikeLike